“That little girl was me.” One of the many twists of the 2020 campaign season was that Kamala Harris wound up as Joe Biden’s running mate after launching what might have been a fatal riposte at him. Of course this attack–you could almost hear the script being unsheathed–was just good politics, although possibly tinged with elder abuse. Biden’s choice to dwell on his bipartisan cooperation with Southern Senators like James Eastland and John Stennis (who but Boomers even remember these names?) was a blunder. Harris making the connection between this chummy relationship and the segregationist attitudes it enabled–to the continuing detriment of “that little girl”–left Biden looking bewildered. The exchange gave Harris her first, and only, real bump in the polls, and it certainly got Biden’s attention. He responded by bringing her inside the tent where, paraphrasing Lyndon Johnson’s famous but unquotable dictum, she would ‘do less damage.’ (Ironic, no?)

In the wake of all that has happened in the months since, this episode is memorable not just for its impact on contemporary politics but also for its deeper historical resonance. It provides a salutary reminder that a quality public education, still universally touted as the route to prosperity for all Americans, has been withheld from many black families.

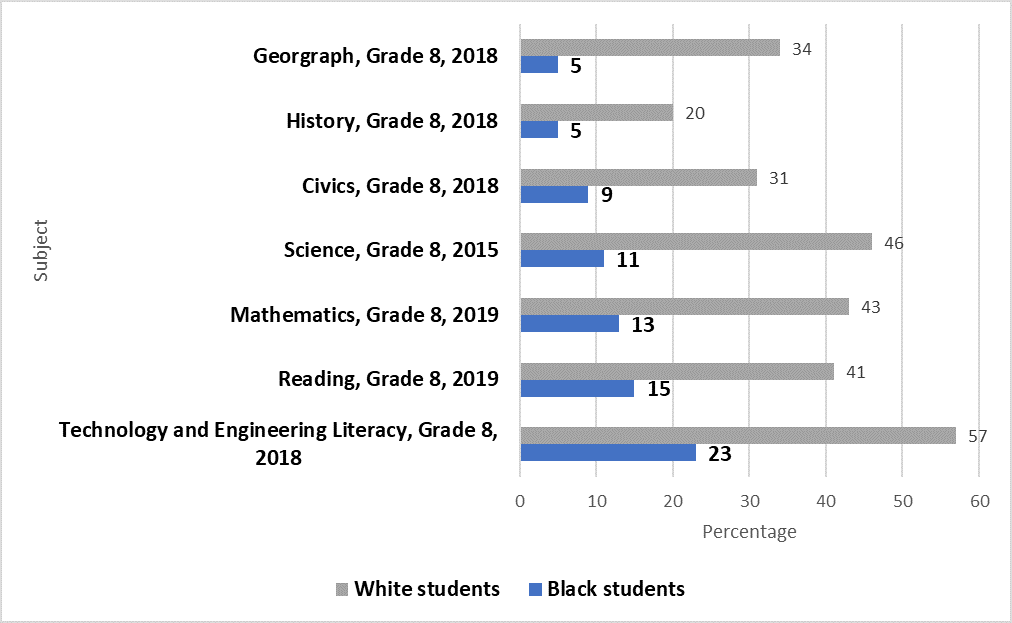

The “achievement gap” between students of different racial backgrounds, in particular, whites and African-Americans

In the long-ago 1970s, the Justice Department and the courts got around to actually enforcing the principle enunciated in the 1954 Brown v. Topeka decision: separate schools cannot be equal. By opposing busing, Biden appears to have opposed the only tactic that has been demonstrated to remedy this inequality. As a child in Oakland, Vice-President Harris got on a bus and traveled to a majority-white school; at the time, this measure was often imposed on reluctant school districts to ensure that black students got access to the same resources . About ten years later, another little girl had the same experience in Waterloo, Iowa. Nikole Hannah-Jones has recently gained notoriety as an editor of the controversial “1619 Project,” but her earlier journalistic investigation of the history of school desegregation is far more thorough and important.

Hannah-Jones’ conclusions, first aired in 2015, underlined the fact that one approach had appreciably diminished the achievement gap: integration of existing schools. It had taken decades for the Brown decision to be taken seriously in the South–and it is now the least segregated region in the country–and by court order desegregation came North eventually. Yet, by 1990, it had effectively been dropped. School districts began to “re-segregate,” with fewer and fewer black students attending schools where they did not already constitute 90% of the enrollment. The end of integration through mandated busing began with a lawsuit in Charlotte, N.C., that pitted a group of black families defending the successful program against the claims of a recently arrived Northerner that race was being used to determine school placements. (Irony alert.) The final ruling, in 1999, declared that “prior vestiges of racial discrimination had been eliminated to the extent practicable,” a situation that most of American society now seems willing to accept.

Leaving aside the interminable debate over charter schools, voucher programs, and the power of local school boards–all of which imply that black parents have options if only they would use them instead of the schools they are already paying for–it is obvious to even the casual Martian visitor that public schools in “inner cities” are inadequate. The real question then becomes whether the institutions that control the necessary resources will take action to offset underlying inequalities in employment, property values, and (yes) educational aspirations, that skew the system from the start. The final irony, for those who still believe in such a thing, is that the matter ostensibly being raised by Harris in July 2019–equal access to education–is nowhere near the top of the Biden administration’s agenda now. Coverage of the pandemic has highlighted the question of racial equity in almost every aspect of life, including public schools–room capacity, masks, remote learning, sports schedules, etc.–without touching on the fundamental inequity in education that existed long before and persists to this day. The much anticipated “return to normal” will also leave it unchanged. If this knowledge makes one journalist a bit intemperate in her description of the Founding Fathers, it is understandable. History can make people impatient.